by Ted Marr, 25th Gen.

Henry, Di Yuen Marr 24th Generation

My father, Di Yuan 地元, was the first person in the Ma family who could read, write and speak English fluently. And, he traveled abroad beyond China extensively even when he was young. Despite the fact that he only had a minimum number of years of formal education in Ningbo, on his own, he mastered English well enough to correspond in English and had the insight to send his children abroad to study during some challenging times in China.

Born in 1890 of the 19th Century, he, in fact, had the foresight of a 20th Century person. He chose the Anglicized English last name MARR rather than the traditional spelling of MA. He adopted an English first name, Henry, when most Chinese did not even know English. He was able to circulate among Europeans in speech and writing. He moved agilely among his circle of American and European business people.

In going through his extensive legal papers, I was able to estimate that he was a wealthy man, a billionaire (in today’s US Dollar value), before the takeover of China by the Communist Party. The 1945 revolution was a major financial hit on him which he penned the narrative in a letter to his four sons. It is attached as a download pdf at the end of of this article. English translation of this letter will be forthcoming later. Reading this letter, even today, you can feel his anguish and pain. While sojourning in Hong Kong to escape the wrath of the communists, he wrote a short Memorandum of his bio which is also attached a s download at the end of this article. Again, in time, i hope we will have an English translation of this letter.

In addition, I have gathered together many of his legal documents in one place. From these original documents, which are available as a downloadable pdf, one can piece together a bit more about this first International Entrepreneur of the Ma family.

A Short Bio

DiYuan 地元G24 was the first person in the Ma family who could read, write and speak English fluently. And, he traveled abroad beyond China extensively even when he was young. Despite the fact he only had a minimum number of years of formal education in Ningbo, on his own, he mastered English well enough to correspond in English and had the insight to send his children abroad to study during some challenging times in China.

Born in 1890 of the 19th Century, he, in fact, had the foresight of a 20th Century person. He chose the Anglicized English last name MARR rather than the traditional spelling of MA. He adopted an English first name, Henry, when most Chinese do not even know English. He was able to circulate among Europeans in speech and writing. He moved agilely among his circle of American and European business people.

At 16-years old, he struck on his own, leaving behind his home in Ningbo City and started his business career in Shanghai’s metropolis at a foreigner-owned lumber company. This is like moving from Omaha to New York City. He was always a pioneer at heart.

In business, he used both his Chinese name 圻源 which he spelled Chee Yuen and the English name, Henry. Due to his smarts and ability to speak English, he rose quickly and became the comprador of the German lumber company, 祥泰木行 Xiang Tai Lumber company. At this young age, representing the company to source lumber, he often traveled to Indonesia.

He was married to his first wife, Miss Yao, at 22; and had his first daughter and first son at 23 and 26. He married his second wife, Miss Yue, at 44. He then had five more children, three boys and two girls, between 47 to 51 years old.

He deftly moved into his major career trek from lumber to importing chemical and dye products from Europe and the US. In those days, chemical and dye are the “high tech products” of that era. He became the General Manager for NanXing Chemical and Dye company 南星染料 doing business in six central provinces in China with Hankou (Hankow) as his headquarters. Hankou is today’s Wuhan. On the Yangtze River, Hankou is in the middle of China, just as Chicago is for the US. It was there Alec and Meiling were born. In fact, until the very end of his business career in China, Hankou was always his business hub. I sorted through hundreds of pages of his old papers and pieced together some of his business dealings. They are summarized in the chart below. Besides chemical and dye, he was also into many different kinds of other businesses, including restaurants, ice manufacdturing, cotton mill, telephony, and real estate. However, his main trade was chemical and dye, which he made a killing during WWI and WWII. He represented National Aniline and Chemical out of Buffalo, New York. National was, until the end of WWII, the largest chemical and dye company in the US. Today, after many mergers and acquisitions, it is now part of Honeywell. Aniline is a petroleum-based synthetic dye, the high tech of the era.

He owned many properties for his extended family in many locations: Hankou, Ningbo, and Shanghai. Most of his personal properties, which he acquired, were later placed in the names of his four male heirs: William, Alec, George, Ted, and his second wife, Yue. Most of the deeds are reproduced as a downloadable pdf at the end of this article.

Based on a preliminary and rough estimate, his total wealth at around 1949 should make him a multi-billionaire in today’s US dollar value. My calculation is based on the actual written documentation. However, the figures in the table need to be tempered by several factors. First, not all his equities are included. These are only the items that I could collate and read from the pile of papers handed to me by Alec. Then, the investment in Meilong Town Restaurant seems to be inordinately large. Nevertheless, even if that number were to be zero, he was still a billionaire. Also, some of his investments may be serial. That means he could have sold some equities and then used those proceeds to purchase other equities. Currently, available documentation is silent on that point. Finally, it is difficult to assess the value of most of the family real estate properties. In general, I believe my estimated value is on the low side. Regardless of how one fiddles with the numbers; Henry either was a nine- or ten-digit multi-billionaire in today’s US dollar term. He was a wealthy man.

He was also active in his business circle. In fact, he was the Chairman of the Hankou (today’s Wuhan) Association of Foreign Trading Companies. During the 1930s and 1940s, there were a lot of upheavals from the Japanese invasion. In 1938, to escape from the Japanese, he stayed briefly in Hong Kong, where Evelyn was born. When he returned to Shanghai, George and Ted were born. During this period, Henry’s patriotism against the Japanese invasion shined when he supervised and coordinated the distribution of propaganda leaflets in English and French to defeat the Japanese’s invasion of China. As a patriot, not only he contributed to the production and funding of the leaflets, he also contributed to magazine publications of the Anti-Colonial invasion of the Japanese.

Then, the Japanese came to Shanghai. Still, because of the Japanese fierce and ruthless occupation, he had to get out of Shanghai. His engagement in anti-Japanese activities put him in a dangerous position. The escape from Shanghai to the countryside was a hallowing experience of which Meiling had a vivid memory. The following section in italics is the recollection of the account by Meiling, my sister or Henry’s second daughter:

It was around the Spring of 1945 when I was around 6 years old. The Japanese had completely taken over Shanghai. Father felt the family had to get out of Shanghai to go to ZhongQing 重庆, in China’s western interior, where the Republic of China’s temporary capital had been setup. The main reason father felt he had to leave Shanghai is he did not want to be branded as a traitor. If he were to stay, he knew, as a prominent member of the business circle’s upper echelon, he would be forced to compromise one way or another. Treason is not a concept he could entertain. He is a patriot.

So, Father, Mother, and all five of us young children plus a few other friends and their children, who are of university age, set out towards the Western Capital, ZhongQing 重庆. Father’s sister’s daughter, MeiYu 美玉, also accompanied us. So, we had a large entourage of about 20 people.

Our first stop was Nanjing, about 125 miles away. east of Shanghai Although this is not very far by today’s standard, it was a big deal in 1940s, and the war was raging. We managed to board a really crowded train. To make sure the children could safely board the train, each of the young children was carried by an adult. There was an enormous mass of frightened crowd at the hectic Shanghai train station.

I remember that after we all had boarded the train, my mother noticed that Evelyn was missing. After a frantic search through each of the carriages, they were able to find Evelyn with her guardian. It was a great relief when she finally reunited with the main group.

After we got off at Nanjing, the group pushed onward towards Hankou, our next stop to ZhongQing 重庆. Everyone walked except us five children who rode on the luggage wheelbarrow carts pushed by the porters. I do not remember how many days we traveled by foot from Nanjing to Hankou. Looking back, I now realize it was a very long way on foot, over 350 miles. In those days, Hankou was one of the tri-cities (Wuchang, Hankou, and Hanyang) today combined to form one gigantic metropolis called Wuhan strategically located on the Yangtze River, a point about halfway between ZhongQing and the East China Sea.

Hankou is an important city for China. It is the hub of major commerce in the southern half of China. Everything upstream coming down the Yangtze river must pass it. Furthermore, Hankou was the city that father made a lot of money. He was a big shot there. He owned a lot of businesses and properties in Hankou. But, his main business is NanXing Chemical and Dye Company. His customers were mills and fabric manufacturers.

Of course, as a 7-year old, I had no concept, at the time, how far we had to walk. We children were just happily riding the wheelbarrow luggage carts. At that time, the Japanese controlled the Yangtze River’s side, where we were trekking through the farm paddy fields. And the Nationalist resistance troops were on the other side of the huge river. The war front was the River. As we slowly made our way towards the front line, it was exhausting; besides being a very long trip, the weather did not help. It was in the late Spring; and, Wuhan is known as one of China’s three “ovens.” It was hot and muggy. At some point along the way, we found we had the Japanese blocking our progress. Simultaneously, local bandits were taking advantage of the helpless refugees and pressured us from behind. These Chinese bandits, if they could, would rob the refugees and locals at every opportunity.

At this stage of the journey, mired in between the forces, our friends, and their university-age children, one by one sneaked across the war front to the other side of the River. So, the refugee group was now reduced to only father, mother, MeiYu, and the five children.

Given the difficult situation, father and mother decided to stop and hide in a village. There we settled down a bit to see what would happen next. During the entire journey, we shed our nice Shanghai city clothing for peasants’ plain and torn clothing so we could blend in. As we hid in the village, mother decided it is time to bring out our weather-moistened but nice Shanghai city clothing to dry off in the sun.

She made a strategic error.

So, on that sunny day, when mother hanged out our nice clothing, we might as well have announced on a loudspeaker that we are wealthy people from Shanghai. The mountain bandits noticed. But, hiding in a mountain near the front, they were not from the Japanese in front of us. These Chinese bandits were cautious not to create too much havoc for fear that the Japanese might come after them. So, they usually laid low during the day.

That same night, they stealthily came to our house in the village. The villagers got wind of their coming and notified us, so father went into hiding for fear that the bandits would kidnap him. Mother thought she would be safe with so many young children.

The hut in which we stayed was tiny, just one room. All of us slept on the same bed, crowded into the same mosquito net. So, there we were, mother, MeiYu, and the five children huddled inside the mosquito net.

After the four bandits came into the hut, mother decided that it is best to treat them nicely. So, she served them tea and cigarettes. I was terrified and hiding with all the other kids and MeiYu inside the mosquito net. Surprisingly, they decided to kidnap mother and demanded that father bring large ransom money the next morning before releasing her. When we heard that, we all started to cry. That bothered the bandits because they did not want our loud crying noise to bring in the Japanese soldiers stationed nearby. So, they let mother come to the mosquito covered bed to comfort us. And, they also ordered her to say goodbye to us quickly. When she got into the mosquito net, she quietly opened up her secrete jewelry belt and handed it to me for safekeeping. Then, she left with the bandits.

The next morning, a message was sent to father regarding the ransom demand. Father had no money with him. As a last resort, the villagers took him on a sampan to a nearby small town to see what could be done. Fortunately, in the town, he found a fabric shop. Even though the owner did not know father, he was aware of father’s name as a big shot in the fabric manufacturing business. Realizing father was desperate for money to save mother, they were very kind and generously lent him the ransom money.

Although I don’t know the exact details of the exchange of ransom money for the hostage, my mother, I was so relieved that mother came home unharmed and assured us that the bandits were respectful and she was not harmed in any way.

We stayed at that village for a while, soon, the Japanese retreated from that area, so we could proceed to Hankou and enjoy our big mansion in Hankou. A little while we arrived in Hankou, the Japanese surrendered in September 1945; mother took Alec and George back to Shanghai. Then, Evelyn, Ted, and I were under the charge of MeiYu. The news came that MeiYu had to return to Shanghai to get married. So, she went back to Shanghai with Evelyn, and I. Ted stayed behind in Hankou with his godmother Leung for a little while longer because Leung has no children. Ted attended a Roman Catholic kindergarten there, and the nuns gave him the English name, Teddy. A little bit later, he also came back to Shanghai. So, finally, the whole family was all united.

Henry was not only a keen student of the Peking Opera, he was also an enthusiastic participant of the arts and religion. He was a lay monk for many years and wrote a commentary on The Prajna Paramita Heart Sutra 般若波罗蜜多心经. Although much of the commentary’s content he took from his notes as he listened to his Dharma Master, he did, in fact, on his own, in a scholarly manner, created an analytic diagram summarizing the teaching of the Buddha. It is attached at the end of the Commentary, which was published when he was 43.

A copy of the commentary and a short write-up could be found here.

He loved Chinese Peking Opera not only as an audience but also as an amateur performer. His “make-up complete actor” portrait and the playbill of that performance have been preserved in a photographic form. It is in the photo gallery. He and his second wife, Yue Pai Yung (my mother), often sang together at home parties among other Peking opera enthusiasts. Much of his Peking Opera singing recordings have been preserved in electronic form. These recording will be available at the later date on this website.

He also has many other interests as well, including earning a certificate in acupuncture, practicing yoga (he can do a hands-free headstand), and playing golf with a handicap of 24.

But, the good life in Shanghai from 1945 to 1949 was short lived. After the Chinese Communists took over the entire China, Henry and his family escaped to Hong Kong. Because much of his money was tied up in real estate and stock in Chinese companies, so he had to leave nearly all his money behind. The whole family hastily fled with, literally, a few suitcases on a chartered plane to Hong Kong. Life was not easy for him having to be reduced from a billionaire to a refugee in Hong Kong. It was devastating. Only in the space of one year, most of his wealth earned over a life-time was taken away first by Chiang Kai-Shek’s government then by the Communists. As he did not bring out much money, life was no longer like the glory days in Shanghai.

In fact, refugee life was very hard for a large family.

It seems some of his wealth in Shanghai was in the form of real gold, actually gold nuggets. But, he had to leave them behind in the hastily unplanned run to Hong Kong as refugees. Again, Meiling was able to provide an eyewitness account as recorded below.

In about 1951, soon after the Chinese Communists took over China when travel between the Mainland and Hong Kong was still permissible. William, our oldest brother who stayed behind in Shanghai, came to Hong Kong. I was surprised to see him suddenly entering our second-floor apartment at 53 Fort Street, North Point, an area where most of the Shanghai refugees stayed. He came into the house with four very heavy crates of tiles. The tiles were packaged in 18-inch wide wooden crates made from heavy wooden slates. After he set the heavy crates down, William and father proceeded to open the crates. Surprisingly, they paid no attention or any interest to the tiles, which were just set aside. Then the two of them progressed to break the empty crates up. Then they further cracked the slates.

I was so surprised to see sandwiched within the slates were many finger-size golden nuggets. I don’t remember how many nuggets. But, I just remembered there were a lot, probably at least several dozens. As our father lost all his millions in China, these golden nuggets were a life-saver. We survived on them in Hong Kong.

After Henry moved to Hong Kong, he sent each of his children overseas for education in short order, all within about a decade. Alec left for England to study Engineering, then Meiling left to be a nurse in London. Then, George and Ted left for University studies in the US. Finally, at 71, Henry emigrated to London with my mother and Evelyn.

After many years, when he was in his 80s, Henry and all the children eventually migrated to the US West Coast. He died in Montreal, Canada, at the ripe old age of 93.

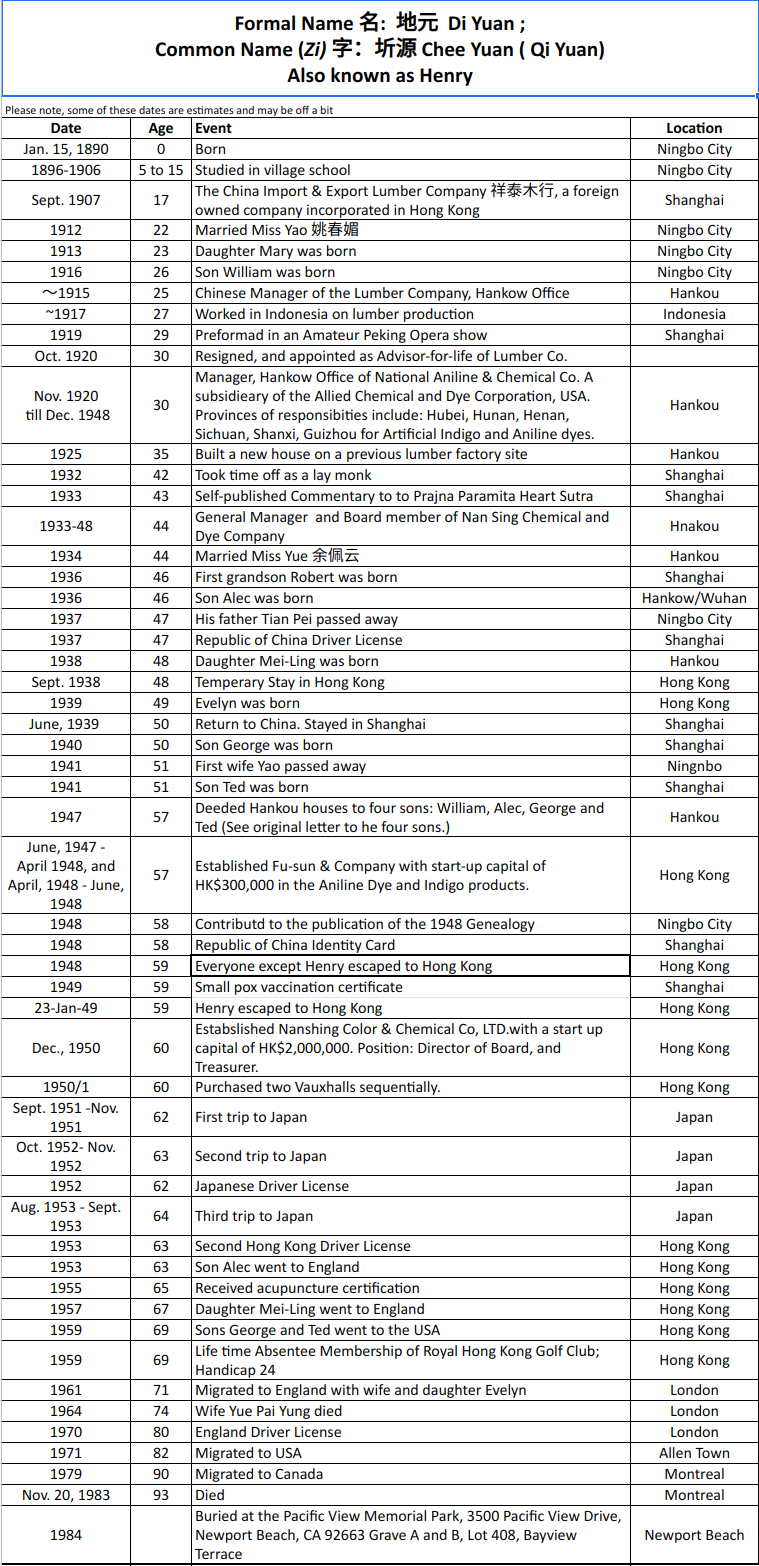

The following is a summary of Henry’s life, chronologically

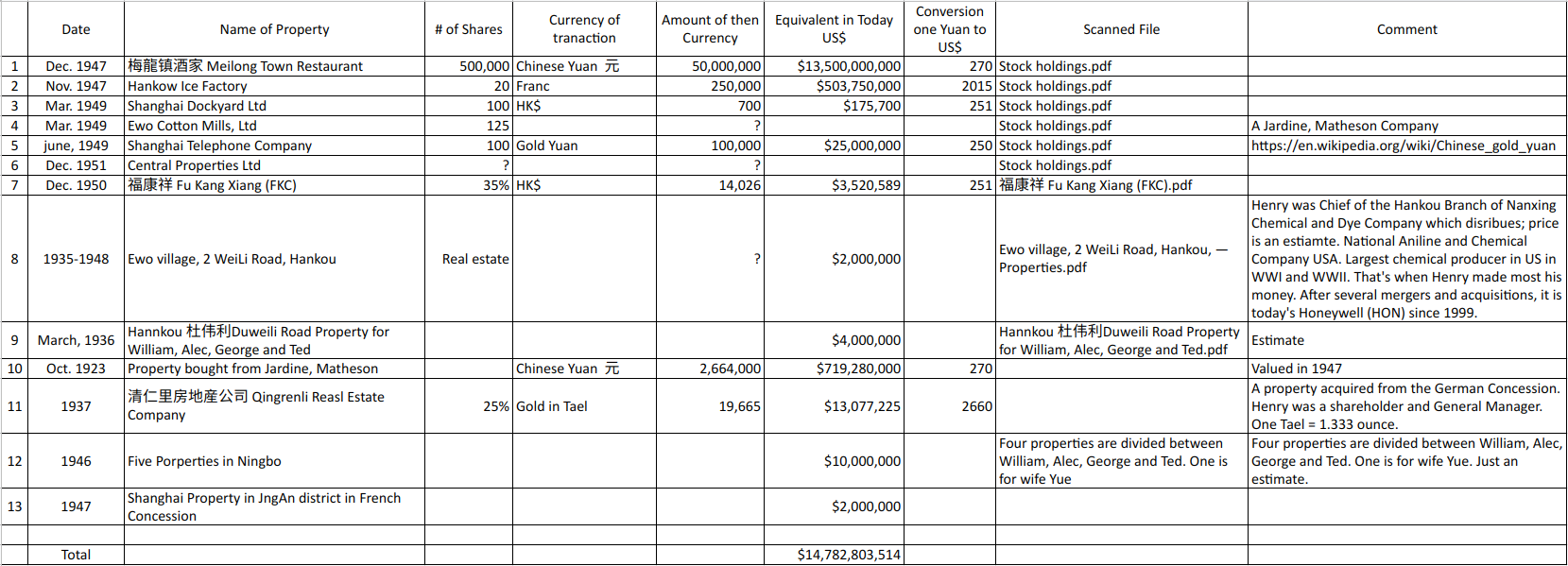

The following is a summary of his estimated equity based on available documents

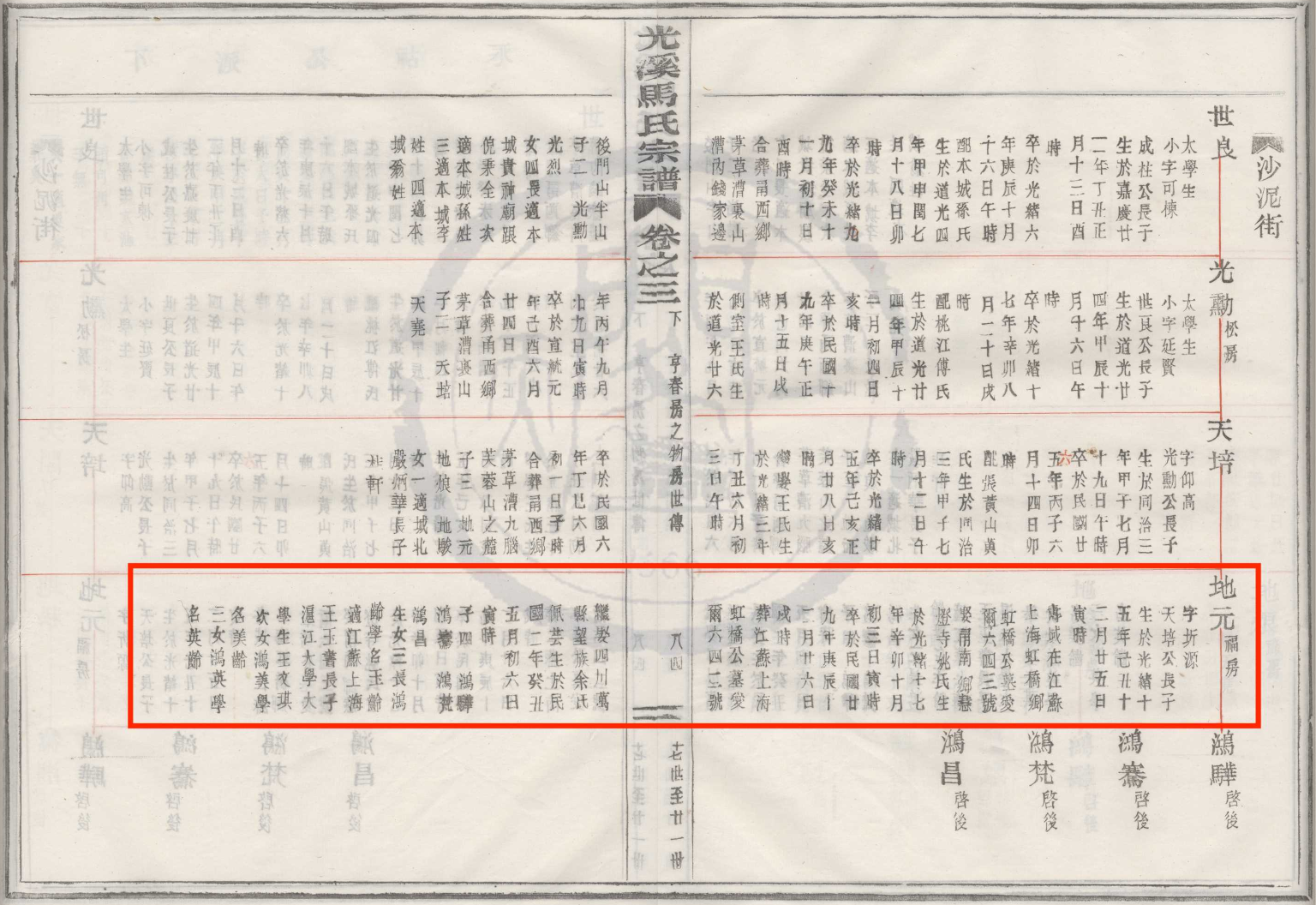

The following is his entry in the 1948 Genealogy on File 2.0203

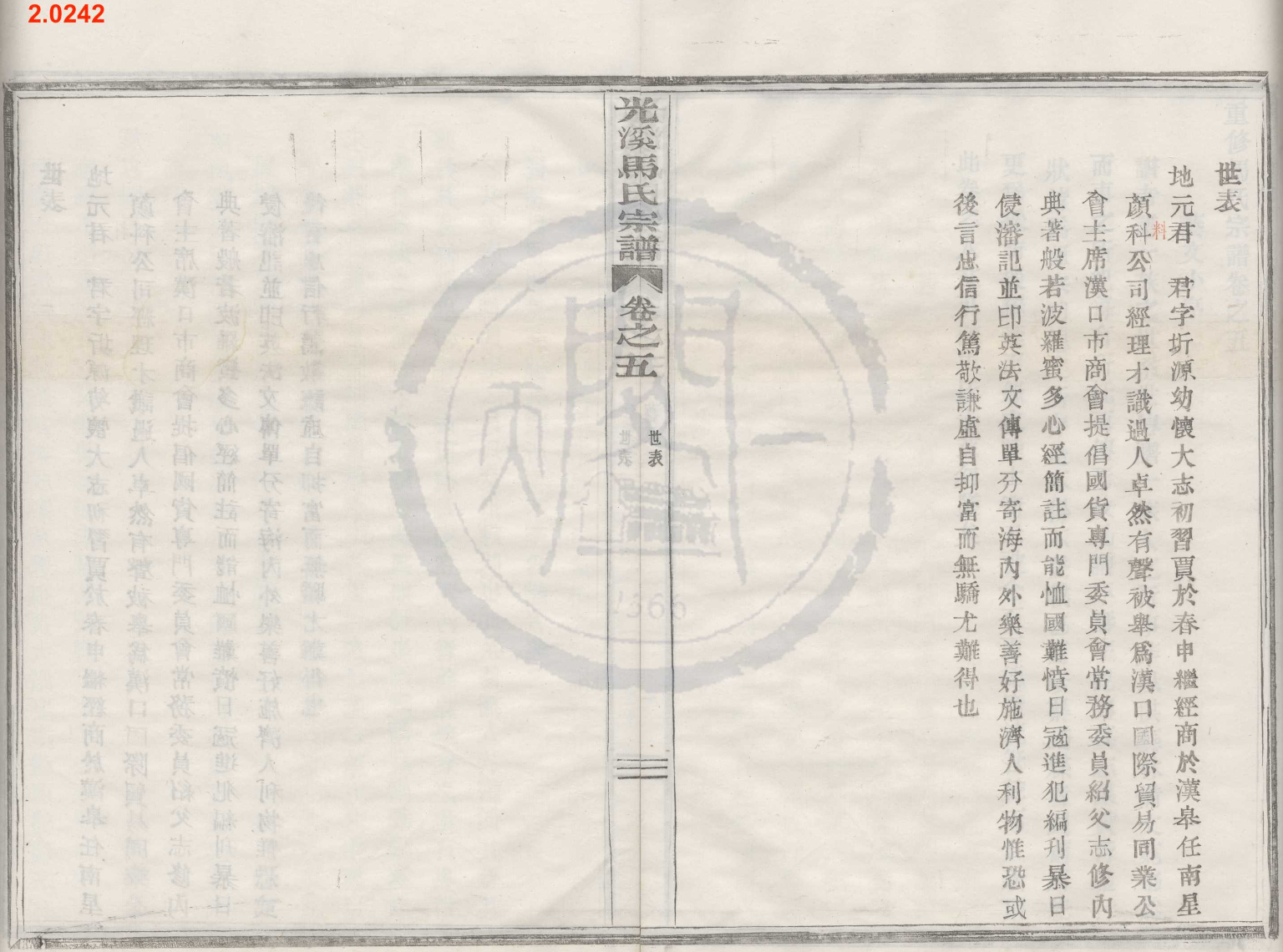

The following is a short write-up about Henry in the 1948 Genealogy on File 2.0242

Letter of Henry’s June, 1959 letter to his son, Alec

- Alec, Henry’s second son, was studying in England at that time. This letter is significant because it reveals several pieces of information not available in the 1948 Genealogy. From his letter, we learned that it was YouCai有才 (G19) who moved our family from Bright Creek to the center of Ningbo City and settled at the large family compound on DaShaNi 大沙泥Street. So, we must have moved from Bright Creek Village to the City Center around 1780. Then, Henry told us that YouCai有才 (G19), ChengZhu成柱 (G19) and ChengCai 成彩 were all buried outside of Ningbo South Gate near Ma Family Creek Village 马家漕村. This piece of information will help us in the future to locate these graves. Finally, we learned that there were four brothers during the Ninth Generation (he mistakenly stated the Tenth Generation), each of whom built a family ancestral temple. Our ancestor was the youngest, or the fourth son ZiWen 子文 (G9), and that temple was destroyed during the Taiping Rebellion in 1850.

Attached below is Henry’s June 1959 letter regarding Genealogy. English translation by Debbie G26.

福龄吾兒,如見。

汝來信要我寄家譜簿。按我族馬姓,自宋朝金之亂,昔時宋皇避難至此地,九龍投海自殺,其地址即今近飛機場,之宋皇台。我族祖先孝寬公,帶族人由河南開封府(即宋朝京城),避金人之亂,遷避至“四明”,即現在的寧波,由孝寬公傳至第十八代子孫,立四房,為子仲(天房),子俊(地房),子鶴(人房),子文(物房),聚居寧波南鄉,百樑橋,建立四座祠堂。我們由物房係傳至今日,不料髪匪之亂(八十年前),我物房祠堂,受火災焚失,故而目下百樑橋,只有天地人三個祠堂,但是家譜,每六十年或八十年修立一次,而二次世界大戰勝利之日,我百樑橋馬氏族長,發起編修 家譜,派族人來上海接洽,籌辦費用,我立即答允補助政費,分期匯幣,已付匯兩次,不料共匪作亂,緻我族大譜無法進行重修重編,而且我心願,想重建物房祠堂,緻一切受共匪之影響,無法可進行耳。我家中,在寧波大沙泥街,第二進閣樓上,有祖宗神碑及縂家譜簿二本。

我們一係,自從有才公,由南鄉百樑橋遷移寧波城内大沙泥街,目今此舊宅,已有百餘年,其所有權,土地証等,均是我的,屬於馬鴻驊 ,鴻騫,鴻梵,鴻昌所公有。

我又在寧波城内,坭橋街,新建西式住宅,其所有權,各寵 鴻驊 ,鴻騫,鴻梵,鴻昌執業。

墳墓:有才公,成柱公,成林公,成彩公, 墓,均在寧波南門外,馬家漕鄉村。

我們一係,再由世良公派傳。

世良公墓,在寧波西鄉,西山茅草漕半山。

我祖父, 光勲公,我父親,天培公,墓,均在寧波西鄉,茅草漕九腦芙蓉山之麓,此墓由我所建,均印有照片,來日面交汝看。

汝大母姚氏之墓,又我的壽域及汝生母壽域共同在上海,虹橋鄉,虹橋公墓L643號,各有照片,來日給汝看。

我們一派,近係,再由我的祖父光勲公(松房)傳至今日。

而馬地勝,地偉,地發 ,他們是光烈公(柏房)之孫子,與我同一個曾祖,世良公,即五族(五代)之内。

我這樣叙述,想汝再讀小家譜,較易明白耳。

我今天交郵挂號,寄給汝小家譜簿一本,該譜簿在1936年,由汝祖父天培公,抄給我的,希汝珍藏之。

對於家中,加丁加女 ,均須記入。

能各自抄譜,更好,此亦即推本思源之順序。

父書字

1959年六月八日

Fúlíng (福龄, Alec), my Son, (this letter to you is like seeing you).

Your letter asked me to send you our family genealogy book. The history of our Ma family begins at the Song-Jin Wars 宋朝金之亂. Sòng Emperor宋皇 took refuge here. He committed suicide at Kowloon. The location is near today’s airport, or now known as Sung Won Toi (宋皇台 or sònghuáng tái).

Editor note: The historical reference is to the chaotic war years of the Song-Jin Wars, then the Song-Jin-Mongol wars. Many battles occurred in/near Kaifeng from 1126-1234; in one campaign, the Jin chased the Song as far south as Ningbo before being pushed back to the north. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jin%E2%80%93Song_Wars

The year 1279 marked the end of the Southern Song Dynasty when the Mongolian army chased the last two child emperors of the imperial Song dynasty all the way South to present-day Kowloon City where the last Song emperor died by suicide by jumping off a cliff into the sea in 1279. The referenced airport was the Kai Tak airport which closed in 1998. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sung_Wong_Toi

When they were running to evade the chaos of the Jin war, my ancestor Xiàokuān (孝寬, Gen 1) moved our clan from Kāifēng 開封 (the Song Dynasty capital city) in Hénán 河南 Province to Sìmíng 四明, now known as Níngbō 寧波. They remained there for 18 generations starting from Xiàokuān (孝寬, Gen 1).

4 Houses were set up for: Heaven House 天房 for Zizhòng (子仲, Gen 9); Earth House 地房 for Zijùn (子俊, Gen 9); People House 人房 for Zihè (子鶴, Gen 9); Matter House 物房 for Ziwén (子文, Gen 9). They settled in 100 Beam Bridge village 百樑橋, Nanxiang 南鄉, Ningbo 寧波 county. Four ancestral temples were built, one for each House.

Editor note: Gen 8 is JiXiui 季修 who has four sons, as listed above. So, in fact, the four houses start with Gen 9. Although to honor their ancestors, traditionally, it would recognize Gen 8 as the starting point because probably Gen 8, JiXiui 季修 is the person who decided.

We are descended from the Matter House 物房 to this day. Unexpectedly, 80 years ago, during the Taping Rebellion (1859), our Matter House 物房ancestral temple was burned during a fire disaster. Of the four Ma ancestral temples, only three (Heaven, Earth, and People) remain at the 100 Beam Bridge Village 百樑橋.

The family genealogy ancestry book is updated every 60-80 years. On World War II Victory Day (“Sino-Japanese War Victory Day”), our 100 Beam Bridge Village Ma family clan patriarchs launched the compilation of a new edition of our ancestral genealogy book. Family clan representatives came to Shanghai to discuss expenses. I immediately agreed to subsidize the cost in installments. I paid two installments. Unexpectedly, Communist bandits create such chaos that our genealogy book could not be revised and updated.

Editor note: It is unclear why he said that the Genealogy book was not updated. In fact, it was completed in 1948. However, it is possible that he was thinking about a new Genealogy book, starting with Gen 21, Shiliang. There are two pieces of evidence that he had a major influence on the editorial content. First, in a rather odd location, there is a short bio about him (2.0203.jpg). Now, he is the only one of the Gen 24 with a short bio included in the Genealogy’s 1948 edition. And secondly, in his genealogy entry, there is the mention of George Wong as his son-in-law who graduated from HuJiang University 沪江大学. There is no other son-in-law mentioned in the entire Genealogy. Therefore, he must be influential in the editorial content.

I desire to rebuild the Matter House 物房ancestral temple, but everything was affected by the war brought upon by the Communist bandits and could not be done.

In my home in Níngbō 寧波on Dàshāní Street (Big Sandy Road) 大沙泥街, on the second floor of the building in the second courtyard, there are ancestral memorial tablets and two copies of the ancestral genealogy book。

Our family line, from Yǒucái (有才, Gen 19), moved from 100 Beam Bridge village 百樑橋Nanxiang 南鄉 to Dàshāní Street (大沙泥街), in Ningbo 寧波 City. We have over 100 years of history at this old house. Its ownership, land certificate, etc. were mine, and I passed them to Ma Hónghuá (鴻驊, Gen 25, William), Hóngqiān (鴻騫, Gen 25, Alec), Hóngfàn (鴻梵, Gen 25, George), and Hóngchāng (鴻昌, Gen 25, Ted) to own jointly.

Also, I had a western-style house on Níqiáo Street (Muddy Bridge Street) 坭橋街 in Ningbo 寧波 City. I lovingly bestowed the ownership to Hónghuá (鴻驊, Gen 25, William), Hóngqiān (鴻騫, Gen 25, Alec), Hóngfàn (鴻梵, Gen 25, George), and Hóngchāng (鴻昌, Gen 25, Ted).

Editor note: The deeds of his four properties in the four sons’ names are avallable to download below. These houses are inn Ningbo city. There is also a property under the name of his second wife, Yue.

Tombs:

- Yǒucái (有才, Gen 19), Chéngzhù (成柱, Gen 20), Chénglín (成林, Gen 20), Chéngcǎi (成彩, Gen 20) gravesites are outside the Ningbo South Gate in Mǎjiācáo Village (Ma Family Marsh Village) 馬家漕鄉村.

- Our family line, descendants from Shìliáng (世良, Gen 21) – The Shìliáng family cemetery is located at the Ningbo West Village 寧波西鄉, West Mountain 西山, Máocǎocáo 茅草漕 (Thatch Grass Marsh), half-way up the mountain.

- My grandfather Guāngxūn (光勲, Gen 22) and my father Tiānpéi (天培, Gen 23) gravesites are at Ningbo 寧波Xīxiāng 西鄉 Máocǎocáo茅草漕 Jiǔnǎo Fúróng Mountain (Nine Brain Hibiscus Mountain)九腦芙蓉山 foothill. I built the tomb. I will show you photos someday when I see you.

Our more recent family line from my grandfather Guāngxūn (光勲, Gen 22) Pine House 松房 continues down to today. The grandsons of Guāngliè (光烈, Gen 22) Cypress House 柏房 are Ma Deshèng, (地勝, Gen 24), Dewěi (地偉, Gen 24), and Defā (地發, Gen 24). They share the same great grandfather Shìliáng (世良, Gen 21) with me. We are within five generations.

Editor note: In Chinese culture, to be within 5 generations is considered close relatives.

I am telling you this so that when you read our short ancestral genealogy book, you can better understand it. Today I sent you by certified mail the short ancestral genealogy book that was hand-copied for me by my father, Tiānpéi (天培, Gen 23) in 1936. I charge you to treasure and protect it. For our family, males and females must both be recorded. Please make a copy to promote our ancestral roots’ remembrance and take it forward in a smooth, orderly manner.

Your Father, June 8, 1959