By Ted Marr, Gen 25. Jan. 2021

The 1948 genealogy includes a eulogy for Tian Pei 天陪, G23, my grandfather. The eulogy contains a description of Tian Pei’s grave location: 西乡茅草漕九䐉芙蓉山之麓伐石竢銘 (Translation: West Village, Thatched Grass Canal Township, Foothill of Nine Brains Hibiscus Hill). It also states that the gravestone engraving is waiting to be inscribed. Tian Pei died on the fourteenth day of the sixth moon of 1937 CE. Apparently, when the eulogy was written, the words on the gravestone had not been carved yet.

From June 11 through June 30, 2012, my Cousin Youling (有龄) and I discovered the tombs of our ancestors from G21 to G23. You can read the original narrative below, where I recorded the details of our discovery shortly after the events. According to the 1948 Genealogy, there are a total of 14 tombs in that same vicinity. So far, I was able to actually locate 6.

Subsequently, Dianah Marr (G26), with her husband Matt and their boys Eric and Evan, plus Debbie Marr’s (G26) children Matthew and Mason, also visited the grave sites on July 13, 2012. On that visit, the children scratching in the mud and found a large tablet with a long inscription about Elder Shi Liang of the 21st Generation. We did not have time to examine it in detail. I quickly read the engraving It included a reference to Elder Shi Liang as an officer of the law and was awarded an Imperial 9th rank title. We need further investigation of the tablet.

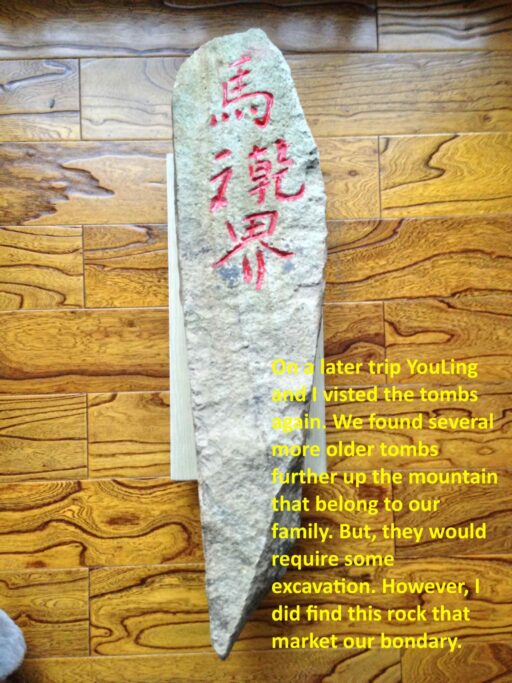

There was also a stone that mark the boundary area of the tombs.

Later, sister Meiling Chan (G25) and her husband, Boon also visited on May 20, 2013.

There is much more to be discovered at this location. One day, I hope someone will continue exploring and excavating these tombs, and find out more about Shi Liang’s tablet and locating the other tombs.

Here is the location of the grave site: Longitude and Latitude 29.888611, 121.380769. in 浙江省 Zhejiang Province, 宁波市 Ningbo City, 鄞州区 Yin Zhou District, 集士港镇 JieSi Gang Town, 四明山村 Siming Village (originally known as 茅草漕乡 Thatched Grass Canal Township), on a hill next to West Ao Dam Reservoir 西嶴水庫(Originally known as the Nine Brains Hibiscus Hill九䐉芙蓉山)

Discovering the Tombs

By Ted Marr, June 2013

The 1948 genealogy had the eulogy for Tian Pei天陪, G23, father Henry G24’s father. The eulogy contains a description of Tian Pei’s grave location: 西乡茅草漕九䐉芙蓉山之麓伐石竢銘. Translation: West Village, Thatched Grass Canal Township, Foothill of Nine Brains Hibiscus Hill. It also stated that the gravestone engraving is waiting to be inscribed. Tian Pei died on the fourteenth day of the sixth moon of 1937 CE. Apparently, when the eulogy was made and the genealogy compiled, the gravestone’s words had not been carved yet. I wonder what it really said.

After we left Tian Yi Ge on Monday, June 11, it was only 12:30 PM, so I showed the details of this eulogy to Cousin Uling.

T: “Do you think we can find this?”

U: “I don’t know for sure where this place is. Years before the Cultural Revolution, my father took another cousin and me to this place. I have some vague memory about it.”

T: “Shall we have lunch and try to find it?”

U: “I am not hungry. Had a big breakfast. We can go now. It’s probably not too far away.”

T: “I’m game and not hungry either. Where do we go?”

U: “It says here, West Village. Let’s go to West Gate and ask an elderly local person and see where that takes us.”

We headed west to West Gate.

Little did I know, Uling’s plan was quite different from what I was thinking.

In about 10 minutes we were at the West Gate. He spotted an older person who looked like a local. In China these days, there is a lot of people movement. Ningbo being a rather prosperous city attracts a lot of job seekers from the hinterland. So it is important to find a real local who would know these places with older names.

I pulled my car to the side, and Uling jumped out. I overheard heard the conversation. (Ningbonese tend to speak loudly; well, actually very loud. There is a saying that goes: When Ningbonese are having a conversation, they sound as if they are quarreling, while when Suzhounese quarrel, they sound as if they are having an intimate conversation.)

U: “Do you know where West Village is?”

Local: “West village is further West.”

U: “How far?”

Local: “Don’t know. Just keep going west.”

U: “Do you know where Thatched Grass Canal Township is?”

Local: “Never heard of it. Go a distance and ask again.”

We started to go west again. We had no idea where we were going. We travelled along Zhong Shan Road West. In every city in China there is a Zhong Shan Road named for Sun Zhong San (aka Sun Yat Sen), founder of the Republic of China. He is a revered figure, much like George Washington is to the United States.

We went for about 15 kilometers. I asked Uling the obvious question.

T: “If you have been there during the Cultural Revolution, how come you have no idea where it is?”

U: “Well, there was no road then. My father took us on a boat, the kind that is rowed by foot. Foot-rowing boat.”

I vaguely recall seeing a picture of foot-rowing boat in an old book once. I recall that it is a small boat.

T: “How long did it take you all to get to it?”

U: “Oh, not very long. Maybe one morning. I don’t remember. It was so long ago.”

I persisted to discover some small evidence of the direction where we should be going.

T: “If you can remember how long it took, and if we can estimate how fast a foot-rowing boat can go, then maybe we can figure out how far it is.”

U: “I have no idea.”

T: “Well, the river or stream must not be too far from a hill or mountain. Do you remember the name of the hill or mountain? It says here it is in the hill or mountain called Nine Brains Hibiscus Hill. Do you remember if that is the name? Do you remember any name at all?”

U: “I do not remember any names.”

We are doomed. This expedition was going nowhere. We have no idea about anything.

So, we drove and drove. Zhong Shang Road became Zhangchun Road (Forever Spring Road). Looking around, I see nothing but newly developed four-lane roads. If there were a grave, it must have been obliterated by now. Dust was everywhere. Not very spring-like. My heart was sinking; I thought to myself, “What a stupid idea.”

Then we came upon an old man standing by the roadside. We stopped. Uling asked him in Ningbonese. He didn’t understand a word. Apparently, he is an old man from a faraway city. It was rather smart for Uling to ask in Ningbonese. If the person could not understand, he would be disqualified right away.

We traveled some more distance. Suddenly we saw two traffic policemen riding together on a motorcycle. A light bulb came up simultaneously between us. The car came to a screeching halt. This time Uling spoke in perfect Putonghua.

U: “Could you tell me where is West Village, Thatched Grass Canal Township?”

Police officer: “You passed it back there, maybe 5 kilometers. Turn around and in about 4 major intersections, turn right. Then ask the locals again.”

That’s an improvement. At last, someone has heard of “Thatched Grass Canal Township.” It does exist!

A quick U-turn. Not many traffic rules in this part of the countryside. Nobody cares. We are heading back.

After about 4 intersections, we saw a young girl riding on a small putt-putt. We caught up to her.

U: “Could you tell us where is West Village, Thatched Grass Canal Township?”

Girl: “I am not sure, but I have heard of the place. Just turn right at the next intersection and ask.”

I finally saw it. Uling’s method works.

Turning off the main road, we went down a small country road, ubiquitous these days in China’s countryside. Throughout China, roads are generally newly built, paved in concrete, and often with plowed fields on both sides. One has to be careful driving as not to drop into the field, for there are no road rails or gutters. Just a two foot drop but it would be a disaster to go off the road and get stuck. I would never drive on one of these roads at night.

The road wound around. We drove about 1 to 2 kilometers. We asked. We drove another kilometer, we asked again. This must-have repeated four times before we found three men, older people renovating a farmhouse.

U: “Do you know where West Village, Thatched Grass Canal Township is?”

A long and heated but friendly conversation began. All four, including Uling, seemed to be speaking at the same time. Even though they were in a wide-open space and I typically understand Ningbonese perfectly well, I could not understand a single word from that group. The decibel was just too high. Finally, one person pointed inside the courtyard and shouted for someone inside the house. Out came an even older person, smiling.

That’s a good sign.

Another round of high decibel discussion. This time, it is accompanied with a lot of pointing in the direction where we were heading. I could no longer control my silence. I tapped Uling on his shoulder.

T: “What are you all talking about?”

U: “This elder gentleman said he is from Thatched Grass Canal Township. He said it is in that direction.”

T: “How far away?”

U: “He said not far.”

The way ‘distance’ was explained by the old man is typical for Chinese villagers. Distance is often described as not far, far, or very far. Not far is better than far or very far. And if they say the far word and follow it with a “Le” particle. It usually means, I am not sure, but it is certainly far away.

It was already 2:30 PM. My stomach was growling.

T: “Let’s go and find it.” I got in the car. But there was another round of seemingly unending set of Ningbonese discussion among Uling and the old villagers.

When Uling finally got into the car, I asked him, “What did you all talk about?”

U: “Oh, nothing really.”

I decided not to pursue the details of that conversation. I would not understand its deeper meaning anyway. We drove east for another ten minutes. Seemingly lost and going nowhere. We ended up in another village. A group of middle age people were strolling along, all dressed in white shirts and dark pants. Uling told me not to ask them because they are just Communist Cadres. They know nothing about locals and even if they do, they would not tell. From the tone of his voice, he did not trust these people.

We pulled up to a house with an open door. Parked the car. Walked up to the house. Sitting in the living room was a young man without a shirt on, reading a book placed on a table next to the window. Uling asked him questions, and he replied politely. I listened carefully and did not interrupt. While pointing in the northerly direction, he said, “I think the next village is Thatched Grass Canal Township. Out of this town, go north on the main road, turn right, and turn right again on the first road. “Thanking him, I noticed the book was a Christian Bible. He was reading the book of Psalms, which is often the favorite book of the Bible among Chinese.

We arrived at the village that we believe to be Thatched Grass Canal Township. I asked Uling if he remembered any of the surroundings. He said no. Along the way, we crisscrossed fields and numerous waterways.

T: “Was one of these the waterways where you took the foot rowing boat from Ningbo city center?”

U: “Probably but I don’t remember.”

Pulling into the alleged Thatched Grass Canal Township, we spotted several people playing Mahjong. In most villages, there are not a lot of people like in a big Chinese city. It is typically tranquil and somewhat deserted during the weekdays when everyone in the village went to work somewhere in the city. Along the entire short block of the village, only four people were sitting in front of their local version of the “seven-eleven” store. They were noisily playing Mahjong.

U: “I am sorry to interrupt you. Is this Thatched Grass Canal Township?” from the opened car window.

Villager: “Yes, it is.” came a definitive answer. I was elated. We have found the village.

U: “Do you know where Nine Brains Hibiscus Hill is?”

Villager: “Never heard of it. Ask Aunt Qian, who runs a store down that street.” He was a little annoyed by our interrupting his Mahjong game. Suddenly, a man with a set of really bushy eyebrows showed up next to the car.

Villager 2: “I will take you there. She is in the store down this street.”

I looked at the street. Clearly, it is too narrow for my Honda CRV. I pulled over to a wider part of the street and parked. Uling and I went down the narrow street, and we were soon joined by many more people who seemingly came out of nowhere.

Aunt Qian was very nice and, of course, loud.

Another round of cacophony ensued. I didn’t want to be left out this time, so I took pictures. Capturing everyone there. People came and went. Soon I noticed Uling was on the local phone talking to someone. Strange. I patiently waited. It is all too much to comprehend. Better wait to find out.

By now, Uling was smiling ear to ear. He told me, “They think they know where the grave is.”

T: “Where?”

U: “Up in the hills.”

T: “Wait, you told me back in the Cultural Revolution Days after you got off the foot rowing boat, it only took you a few minutes to get to the grave. If it is up in the hills, which seems to be at least a few kilometers away, you must have walked a long distance.”

U: “Maybe we did. But I was young then so the distance seemed very short.”

T: “How do we get there? Can she tell us?”

U: “She doesn’t know. I talked to her husband, who is away on business and would not return until this coming Friday. But, let me see if I can persuade her to take us to the water reservoir?”

T: “What water reservoir? That was never mentioned in the Eulogy.”

U: “Well, they flooded the stream, dammed it and formed a reservoir. The graves might have been flooded.”

T: “Wow, all this for nothing. So close and so far away. Are you sure it is destroyed?”

U: “She said some of the graves in the lower section of the hill were moved to another place. But she thinks there is a big one still there up on the hill. Maybe that’s Tian Pei’s grave. I want to ask her to take us to the reservoir and take a look.”

More high decibel dialogue. Suddenly, the bushy eyebrow man walked behind the cash register counter, and Aunt Qian emerged to the street. By then, I had already captured with my Nikon the street sign on the store’s door. It said 宁波市 Ningbo City, 鄞州区 Yin Zhou District, 集士港镇 JieSi GangTown, 四明山村 Siming Village, #31 茅草漕街Thatch Grass Canal West Street. I wonder where are the Central and East sections in this small village.

Clearly, the village is now called Siming. What happened to the Thatch Grass Canal Village? The name of the village is now the name of the street? So many unanswered questions. Apparently, she doesn’t know where Nine Brains Hibiscus Hill is. Why is she taking us to a different hill?

The three of us got into the car, and in five minutes, I saw a dam. On the dam, four bold Chinese characters in concrete relief marking the Xi Ao (West Ao) Dam 西嶴水庫. Wait, I remember reading the name “Ao” somewhere in the genealogy. I can’t recall where. That word is very familiar. Maybe I will find out more about this later.

Soon the main road turned into a dirt road, and then the dirt road disappeared.

I pulled the car over to the side. Aunt Qian got out and waved us to follow her. We walked for one minute. She pointed to a section of the hill full of trees and impenetrable underbrush. I followed her finger, and sure enough, there was a tiny opening in the brush and a very faint dirt path. But she would not move forward.

“I don’t know where the grave is. My husband knows. I cannot go up there. Too much underbrush.”

I said to Uling, ”Let’s give it a try. We’re already here. Maybe we’ll get lucky.”

Without waiting for an answer, I forged forward, charging into the semi-open path. After about 50 steps, the path got a bit wider and clearer. Then the trees and bushes got thick again. I kept going. Uling, following at least 30 steps behind me, shouted for me to stop. He was a little concerned. I was too excited; I want to find Tian Pei’s grave.

After about 20 minutes, the path started to wind upwards steeply. I said to Uling, “How come you said it was just at the bottom of the foothill. We must have driven quite a long distance up the reservoir and now a long way up the hill. Did you really walk a short distance after the foot rowing boat ride?”

U: “I don’t know. I just remember it was not too long a walk. Maybe I was young.”

By then the path was nearly non-existent. I decided it is too dangerous and too difficult. We have to turn back.

We did. And rejoined Aunt Qian.

Getting back into the car, we drove her back into the village. Uling said he would call her and set up an appointment next week to see if her husband can take us.

We returned to Ningbo city. By then, it was already 5:30 PM. We had a deservedly sumptuous dinner at a Ningbo style cafeteria and went home.

During the week following our adventure to Thatch Grass Canal Village, which is now the Siming Village, the weather has turned into “Yellow Plum Weather.” During this time of the year, it rains a lot, and it is very hot.

From mid-June to mid-July, in this part of China and Asia (including Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Japan), there is a weather pattern traditionally called by the Chinese the “Yellow Plum Weather.” This phrase goes back a very long time in historical records to the Tang Dynasty and even earlier.

The weather is characterized by a lot of rain and is very hot. It is the period between Spring and Summer, from mid-June to mid-July. This kind of weather produces a lot of mold. In earlier times and even today in almanacs, this period is referred to as “Entering the Mold” period and “Ending the Mold” period. Chinese almanac periods are often tied to the agrarian culture. Enter the Mold period is also the time when “the grain” appears. It is also an important period for farmers to make sure the rice grains are starting to form. This is well documented in historic almanacs.

It happens that the words mold 霉 and plum 梅 sound the same in Chinese. They both are pronounced “Méi”. In fact, the word Mei or the plum 梅 variant is also CC Marr’s Chinese surname. It also coincidentally is the yellow plum season. Historically, the period is called the Yellow Plum Season 黄梅季节 (Huang Mei Ji Jie) or Yellow Plum Weather 黄梅天气 (Huang Mei Tian Qi) and the rain is referred to as 梅雨 (Mei Yu) or 霉雨. Many historic poems were handed down from famous poets either praising or cursing Mei Yu.

Sunday, fully six days have passed since our initial adventure to find Thatch Grass Canal Village. It had been raining rather heavily the two days before I got a call from Uling, “We should visit the graves on Tuesday if the weather is okay.” We agreed to talk on Monday.

I spent the entire Monday getting ready for our second expedition. I was determined to find the site on Google map. After nearly three hours of hunting, I believe I located it on Google. I mapped out the route. When I called Uling to set up a time and place to meet on Tuesday morning, he told me the good news.

U: “I called Aunt Qian and talked to her husband. He asked me what the name of the ancestor clan is and where we are from. I told him the Hundred Beam Bridge Ma Clan. The husband confirmed that the graves he knew of were indeed for the Hundred Beam Bridge Ma Clan”.

I couldn’t believe the good news! My hopes are raised again. But my hopes had been raised many times before, and each time they fell flat. However, that morning, I found two old pictures of the graves of some ancestors. In one of the pictures, father Henry was standing there. These gravestones were erected in 1922. I was able to see the names of Tian Pei天陪 (G23) and Guang Xun光勳(G22). The large tombstones inscribed with their Zi 字: Yan Gao 仰高 and Ting Xian 廷䁂, respectively. (Historically, when Chinese males reach a certain age, they have acquired other names. Their Zi 字 is usually the name chosen for others to address you.) Although I cannot make out the person’s name in the middle, I am sure it must be Shi Liang世良. I would bet it is inscribed with his Zi 字, which is Ke Kang可棟.

I compared the two mountain range peaks in the picture’s background with the one I took last Monday. Although I can’t be sure, they sure look deceptively similar. There is more vegetation today than there was nearly a hundred years ago. My heart started to pump real fast, thinking this could be it.

Uling and I agreed to connect on Tuesday morning to see if the Ningbo weather is good enough for us to trek up the hill. It is the Yellow Plum Season, and one can never tell.

That night, I did not sleep well. I wondered if Indiana Jones ever had sleepless nights before he went on his treasure hunts. Did he sleep well on the eve of the Crystal Skull? Foolish thoughts.

On Tuesday morning, I called Uling at 6 am. It was not raining in either Hangzhou or Ningbo, but it is forecasted to have periodic drizzles throughout the morning. I did not want to spend another anxious day and night wondering if the graves are there or not. However, Uling also wanted to find out if he could find the graves he visited during the Cultural Revolution. The decision – Go!

Now reviewing the genealogy, I found there were references to six burials in Thatch Grass Canal Village: Shi Liang世良 (G21), who was the common ancestor to Uling and me, both of his sons (G22), and three out of five of their sons (G23). No one in G24, father Henry’s generation, was buried in Thatch Grass Canal Village. So, for both Uling and me, our grandfathers, great grandfathers, and our common great-great-grandfather were buried at Thatch Grass Canal area 茅草漕.

I packed everything that I can think of. Except I don’t have a whip and a hat. Indy would have brought those along.

By 6:50 AM, I left my place. I took the quick route, West Lake Tunnel, and got out of town in a hurry. I called Uling and asked him to get some incense, and all the paraphernalia needed to commemorate our ancestors. We were to meet at Tian Yi Ge, which is only five minutes from his home.

By the time I reached Shaoxing 绍兴, it had started to rain. It continued to rain heavily for the next hour. I can’t imagine trekking up that mountain in that heavy rain. Well, worse comes to worst, we will talk to Qian Shifu and get some info. (In China, there are several forms of polite honorific forms. Shi Fu literally meaning Master Craftsman and is always a safe bet for any working-class people.)

By the time I reached Ningbo, the rain had stopped. Uling with incense, candles, and food for the ancestors, and I was on our way to Siming Village. Using Google Map, I had mapped out the shortest route to get there. Uling had no idea how to get there. He kept suggesting that we should stop and ask. I assured him I know the way. It only took us 35 minutes to get to the village. When we drove down the main street of Siming Village, Qian Shifu was sitting on a bench waiting for us. He had two hoes, a machete, and a machete holder. He is very friendly and forthcoming.

Quickly we drove up the hill, past the reservoir, and arrived at the same spot where I parked eight days ago. There were several locals there. Qian talked to them and learned that they were collecting Yang Mei fruit杨梅from the wild Yang Mei trees. Yang Mei is a subtropical tree grown for its sweet, crimson to dark purple-red, edible fruit. This is not only the Yellow Mei season but also the Yang Mei season.

While driving to the site, Uling and I queried Qian on the graves. I showed Qian a picture of the Tian Pei and Din Yen graves. He could not recall if these were the ones. After a long conversation with Uling, it seems there were two possibilities for the alleged graves that Qing knew about. Either it could be Uling’s, or it could be our branch of the family.

With Qian leading the way, we headed up the hill. Qian hacked away any tree branches or bushes that were in our way. Less than 100 steps into the trek, Uling said,” Hong Chang, your shoe soles are loose.”

I looked down and found both of my nice hiking boots have flopping soles. This is really bad news. Upon examining the boots, it is clear that if they come off, I might have a rather leaky set of boots. The ground was very wet. What to do?

Qian smiled and said, I have a “native method.” He cut off a small branch of a nearby bamboo plant using his machete, which grew everywhere on the trail. He quickly fashioned two very strong bamboo strings. He tied them around my boots, and the floppy soles are now held in place. How ingenious and quick thinking. These locals have their own way of dealing with problems. We, alleged civilized city folks, were certainly fish out of water in this environment.

We passed many Yang Mei trees loaded with ripen fruits. They were delicious. On a different occasion, I would have loved to linger and enjoy the fruits. Not today. After a handful, we moved on quickly.

The trail got wetter and wetter. Several times we had to ford small creeks. Many times, we had to lay down tree branches and leaves so our shoes do not sink into the deep mud. This reminded me of the time we hiked in the Amazons. On we went for over 40 minutes, and the hills got really steep and slippery. I was carrying the backpack and two bags of incense and food/fruit for our ancestors whose graves were nowhere to be found. Uling soon started to complain and kept asking how far to go. He must have asked Qian the same question every 10 seconds. I noticed he was breathing very heavily.

T: “Are you okay?”

U: “I am very tired. I have never worked this hard for a very long time. This climb is too much for me.”

T: “You have a weak heart?”

U: “Yes.”

I am now worried. What if he collapses in the middle of this jungle?

T: “Maybe you should slow down and take a rest.”

U: “This is not right. I know the graves for my grandfather is lower. It can’t be so high.”

T: “If that’s the case, maybe what Qian is looking for is my side of the family.”

Uling stopped, standing next to a tree stump on a very steep hill while Qian and I forged forward. The two of them kept talking to each other, so Uling was always within earshot of us. But his voice got fainter after we climbed for another 10 minutes. I asked Qian if we were going in the right direction. He said he is certain.

Another 10 minutes later, I could hardly hear Uling’s voice down there. By then, I think Qian was beginning to doubt himself. So he said to me, “Why don’t you wait here? I will go and explore to find the graves. I know the Ma graves are not very far from the Qian graves.”

“What Qian graves?” That’s the first time I heard about the Qian graves.

He explained that there is a set of graves that was set up in the 1950s for his grandfather and father. These graves are not far from the alleged Ma graves. Off he went to the right. He kept talking so I could hear him. Soon his voice got fainter and seemed to come from down the hill.

There I was, standing on a very steep hill in the middle of a dense forest. My only company was spiders, mosquitoes, and the dampness. One of the bamboo ties holding the soles was already gone. Uling was exhausted and couldn’t move another step. I wondered if Qian and I could carry him down this steep, wet hill. It is beginning to seem hopeless. I guess I am no Indy.

Then I heard Uling shouting to me, saying that Qian has now circled to a spot below him. Qian’s voice started to float from the left. He had made a very wide circle to see if he could find the graves. Only our faint voices carried through the thick forest were connecting the three of us. This must have gone on for another 20 minutes but seemed like an eternity.

Suddenly, I heard a very loud voice pierce through the forest in Ningbonese: “Ngo shing sut la, Maw ga feng!” – I have found the Ma Family graves!

Fantastic! The voice was coming from my left. A fairly long distance away. I started to move laterally to the left. Cutting through the thick forest, pushing away the branches, and ignoring my nearly sole-less boots, I moved as quickly and as carefully as I could. In about 50 meters, I came upon a small grave. The first grave I had seen today. But, it is not ours. It belonged to some Lu family.

Suddenly, I saw Qian emerging from between the branches. He waved at me to follow him. In the meantime, Uling was also shouting that he is coming over. Totally forgetting my boot problem, I charged forward. In another ten steps, among very thick branches, I spotted lichen-covered stones. This is straight out of an Indiana Jones movie… A Hollywood scene with Indy charging through the forest to find some lost city of gold. But this is more precious to me than gold. I have found the resting place of my ancestors!

I could not believe my eyes. There in front of me are the exact two big tombstones of Tian Pei on the right and Din Yen on the left (right and left has to be positioned by looking away from the graves). Din Yen is G21, and Tian Pei is G22, so the positions are correctly laid out.

The thrill of actually seeing the huge tombstones that are nearly one hundred years old and hidden for such a long time is indescribable —such exhilaration.

Soon, Uling also arrived, albeit a bit breathless. If he had any disappointment that these were not his side of the family, I could not tell; he hid it well. The three of us quickly cleared the trees, bushes and set up our ancestor commemorating ceremony. We lit the incense, the two candles, place the red and white cakes, apples, peaches, and yellow plums neatly in an array. Uling and I took turns to bow and, of course, took pictures. We burned the paper silver ingots so the ancestors could have money to spend in the netherworld.

Both Qian and Uling said, they don’t believe Tian Pei was really buried here. The tomb was set, but by all indication, his body was never interred here. I need to research this some more. Only Din Yen was buried here.

The center section, as it turned out, was not Shi Liang’s tomb. Rather it is a tablet that contained a short history of Din Yen and Tian Pei. The words were hard to read. After a long time, I was able to figure out that they contained no new information except for two things: Ting Xian was a military officer of the fifth rank of the Ningbo Yin County, and the Ma clan moved away from Hundred Beam Bridge to Ningbo City during the time of Ke Quan (G18), probably around the 1750s. The family settled at the Big Sand Clay Street, Ningbo, but they must have remained in close contact with the Hundred Beam Bridge clan.

Suddenly, we noticed a huge yellow butterfly. Almost as big as a Monarch. It hovered over Uling, over me, and here and there on the food. It did not hover over Qian. Is this the soul of the departed Ting Xian? Is he welcoming us to visit him after 130 years? The yellow butterfly did not seem to be afraid of us at all. It kept fluttering around us. It was never bothered by our constant action to clear the place and organize our ceremony.

Could this really be the reincarnation of Ting Xian who died in 1880?

The original gravesite had a waist-high concrete wall around it. It is all gone. Several of the decorative concrete tablets were also gone. The crown on the centerpiece fell behind it. In the original picture, there were open fields. The graves are now deeply hidden in a thick forest.

We took a lot of pictures. By 1 PM, after having lingered there for a long time, we descended. We put out the incense and candles, left the food for the ancestors, and departed. Qian showed us the route we should have taken. It actually had stone steps, albeit somewhat deteriorated by now. Qian said there used to be a concrete handrail. During the “Great Leap Forward” time, when Mao exhorted everyone to produce backyard steel, the rails were removed to rebar inside the concrete. The concrete wall around the graves suffered a similar fate.

After about 100 feet of descent, we came upon the family graves of Qian, which were built around the 1950s. He was pleased that he had an opportunity to visit his family graves.

When we descended to the spot where we veered to the right, we should have veered to the left. Much of the stone steps disappeared. They were probably washed away by decades of rainwater. We moved very quickly down the hill. By then, both of my boots had lost their bamboo strings, and I flopped all the way down the hill. Luckily, the boots did not leak as we waded through creeks and thick mud.

When we arrived back at the Honda, there were hoards of people from the city near the dam. They had come to pick Yang Mei. Standing among them was an elderly man, trying to stop them from picking the Yang Mei because they belong to the village.

Qian went to him and introduced us. He turned out to be the Designated Keeper of the Siming Village Ancient Artifacts, and the Ma graves come under his protection and jurisdiction. He explained that if we want to restore the tombs, we must get permission from the Ancient Artifact Officer of the Ying County, who happens to be a distant cousin of his.

The Artifacts Officer also told Uling that he thinks there is a set of grave headstones near the hill’s lower section. From what he said, Qian concluded that it is where we stopped to eat our Yang Mei. At this point, Uling was too tired from the climb to go back in there to look. We would have to come back on another day to find the graves of his branch of the family.

After exchanging information, we went back to the Siming Village. After I parked the car behind the village next to a beautiful creek, Qian said, “You know this beautiful creek is the Thatch Grass Canal.” Both Uling and I were amazed that we have finally found the namesake of the original village.

At Qian’s store, where we had our instant noodles for lunch, I finally was able to ask a lingering question.

T: “Do you know where is the Nine Brains Hibiscus Mountain?”

Qian: “That’s where we were.” in surprise

T: “Why is it called that name and how come no one seems to know it?”

Qian: “When I was young, my grandfather told me that is the name for this area. You see, in the olden days, the mountains were pretty bare, and they looked like brains. There are nine mountain peaks, and they were named Nine Brains. These mountain peaks are arranged in a perfect circular shape very similar to a hibiscus flower’s petals. Therefore the name Nine Brains Hibiscus. However, no one uses that name anymore. I learned this from my grandfather a long time ago.”

T: “How long has your family lived here? You also told me that your family used to live up near the dam. What is the story behind that?”

Qian: “You see I am the seventeenth generation of my family. We have been living here since our first generation. We used to own the entire set of hills below the Nine Brains Hibiscus Mountains. When the Communists came, we gave it back to the government. Either that or lose our heads which is what happened to others in the neighboring hills. When they created the dam, we had to move to the lower level where we are now.”

T: “That’s too bad. Tell me more about what your family and previous generations did.”

Qian: “For generations, we provided land for burial. This area is very auspicious for graves. Your family must have consulted with Feng Sui masters and chosen the plot. Your family must have been very rich to have chosen a higher ground. Our family, probably my great great grandfather must have been the one that built the graves for your great great grandfather. This has been our family business for generations.”

I realized I am sitting at the home of the descendant whose ancestors actually built Din Yen’s grave. Life is so interesting.

After lunch, we went to the Office Building of the Siming Village. There were two young staff members there. They opened up a few computer folders full of jpg pictures of tombstones removed when the dam was built in the 1950s and those that were removed in 2008 when the new Taoyuan Bay Recreational and Holiday Resort Development project was launched. The government has decided to invest 15 billion in RMB (that’s 2.5 Billion US Dollars) to develop the West Ao Dam area. If Qian is right about this figure, it’s a huge development project. So they removed all the graves at the lower level. Ours is sitting high, so they left it alone. It is not certain if they may not decide to remove them later. A discussion with the Artifact Officer of the Yin County may be an important next step.

Uling and I reviewed all the pictures of the tombstones that were removed. Unfortunately, we did not see any tombstones of Uling’ s family. Rather disappointing. I noticed at least a dozen tombstones had either a Christian cross on them or a reference to the Christian faith. It got me wondering if any of these departed people were related to the young man who pointed our way to the village.

On the way back to Ningbo, Uling and I both marveled at how great things turned out today. It never rained after I arrived in Ningbo. I think Indy would have been proud of how well I handled the treasure hunt.

So here is the location of the grave:

浙江省 Zhejiang Province, 宁波市 Ningbo City, 鄞州区 Yin Zhou District, 集士港镇 JieSi Gang Town, 四明山村 Siming Village (originally known as 茅草漕乡 Thatched Grass Canal Township), on a hill next to West Ao Dam Reservoir西嶴水庫(Originally known as the Nine Brains Hibiscus Hill九䐉芙蓉山).

And, to find it on Google Map, just enter this Longitude and Latitude info in the search box: 29.888611, 121.380769

You can download this page as a pdf here.